A Guide to Brewing Techniques and Teaware

- Katrina Wild

- Jun 13, 2024

- 16 min read

Updated: Mar 8

Tea is not just a beverage; it's an experience, a ritual, and an art form. Different cultures over centuries have developed unique methods of brewing tea, each with its own specialised teaware. In this blog, we will explore some notable brewing techniques and the associated teaware, including Chinese gong fu cha and yixing teapots, gaiwan, senchado and Japanese tea brewing, Vietnamese and Korean tea ceremony, Russian samovar, Occidental methods, Turkish çaydanlık, and modern innovations like iced, cold brew, aeropress, syphon, V60, Chemex, and nitro brewing.

Photo: Seoraksan, South Korea. Cup by Korean pottery artist Junbaek Kim. Katrina Wild.

Tea is nothing more than this: heat the water, prepare the tea and drink it properly. That is all you need to know."

Sen no Rikyū

Well, while the profound and rustic simplicity implied here by the well-known tea master who came up with basic principles for "the way of tea" (chanoyu, particularly wabi-cha), this statement also means presence and attention to detail. As we delve into the art of tea preparation, it's important to remember that it is a deeply personal experience. Learning is an integral part of this mindful process, so let’s explore the diverse array of tools in the world tea toolbox to find what suits you best. Just as one artist excels at painting landscapes with oil and another at portraits with charcoal, the variety of teas, teaware, brewing methods, and ceremonial styles is vast. In a previous blog, we examined how water quality influences the taste of tea, highlighting the importance of every detail in the tea-making process.

Photo: Japanese Tea Marathon, Tabu Tea House, Riga, Latvia. Katrina Wild

Teapots and Materials of Teaware

Let's start with teapots, arguably the most essential tool for brewing tea. Teapots come in various shapes and materials, each associated with specific cultures and rituals. Here are some basic tips on how to choose a suitable teapot for your needs.

Choosing a Teapot

The art of pottery, much like the art of tea, involves a myriad of manufacturing techniques and quality standards, resulting in a diverse range of teapots available on the market. Here are the main factors to consider when selecting a teapot.

- Material. The material of the teapot significantly impacts the tea's flavour. Glass, cast iron, clay, or ceramic are common options. Ceramic and enamelled cast-iron teapots are versatile, suitable for most tea types. Clay teapots, being porous, are ideal for black, puerh, and oolong teas, as they absorb and enhance the tea's flavours over time.

- Size. When it comes to teapot size, smaller is often better. Delicate teas require a small amount of water to fully release their fragrances. As a Chinese proverb suggests, "the smaller the teapot, the better the tea." However, some teas taste better in bigger teapots, let’s say if you are brewing some black tea Western style in a bigger porcelain teapot or your daily sencha in a kyusu that is significantly bigger than your shiboridashi or hōhin. Hence, the size really matters on the style of tea you are going for and for how many people you are infusing for.

- Shape. The shape and handle of the teapot should feel comfortable in your hand. It's important to lift the teapot before purchasing to ensure it pours well and has a comfortable grip.

- Quality. A good-quality teapot will age gracefully. Be cautious of cheap teapots, especially those made of cast iron or clay, as they may deteriorate quickly.

Photo: Wistaria Tea House, Taipei, Taiwan. Katrina Wild.

Before diving into specifics like Chinese Yixing clay teapots and Japanese kyusu shapes, let's explore some common teapot materials:

- Glass Teapots. Glass teapots are neutral and versatile, similar to ceramic teapots. Their smooth surface is ideal for infusing all types of tea without affecting the taste. The transparency of glass allows you to appreciate the unfurling leaves and the colour of the infusion. Most glass teapots come with an infusion strainer, which can be removed when using tea bags.

- Ceramic. It is highly regarded for its quality and finesse. Ceramics include a broad range of materials made from clay, porcelain and other raw materials, which are shaped and then hardened by heat. There are glazed and unglazed ceramic teapots. The glaze on these teapots generally makes them versatile and suitable for all types of tea. They are especially recommended for delicate teas like white teas and Chinese green teas, known for their subtle and nuanced flavours.

- Enamelled Cast-Iron Teapots. Originally used in China as kettles, enamelled cast-iron teapots are suitable for many types of tea. The enamel coating makes them easy to clean and prevents the tea from coming in contact with the cast iron. How-ever, they are not recommended for delicate teas.

- Metal Teapots. Metal teapots vary widely in quality. North African metal teapots are excellent for brewing mint tea and strong, sweet black tea but may impart a metallic flavour, making them unsuitable for delicate teas. Stainless steel teapots are the best choice among metal options due to their durability and neutrality.

Photo: Amazigh Tribe brewing tea on fire called zarda (Siwa Oasis Western Sahara) and Red Lahu Tribe’s kitchen (Doi Mu Puen, Thailand). Katrina Wild.

Gong Fu Cha: The Art of Chinese Tea Brewing

The Memory Teapots: Yixing

Yixing clay teapots, hailing from the Chinese county of Yixing in Jiangshu Province, are renowned for their unique qualities and historical significance. The tradition of crafting objects from Yixing clay dates back to the Han dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE), but significant production of Yixing teapots began around 1500 during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). By the late 17th century, these teapots had made their way to Europe, where they became highly sought after.

Yixing, located west of Shanghai, is famous not only for its high-quality clay but also for the exceptional creativity of its potters. Production centers around the Dingshan community, where both small artisan workshops and large manufacturers produce these esteemed teapots. The craftsmanship of Yixing teapots involves shaping the clay entirely by hand, a process rarely aided by pottery wheels. These teapots, often referred to as "memory teapots," are crafted from porous clay that "remembers" the teas brewed within them. This characteristic allows the teapots to enhance the flavour of each subsequent infusion, making them ideal for black, oolong, and puerh teas. As the teapot is used, its sides absorb tannins from the tea, creating a layer that enhances the teapot's ability to bring out the tea's aromas over time. This buildup of tannins is what gives the Yixing teapot its "memory."

There are three main types of Yixing clay: zisha (purple), hongni (red), and banshanlu (yellow). Each type of clay has distinct natural properties:

- Malleability. The clay's pliable nature allows artisans to craft teapots entirely by hand.

- Porosity. The porous quality of the clay means that a Yixing teapot should be dedicated to a single type of tea to prevent flavour contamination.

- High Ferrous Oxide Content. This gives the clay a distinctive appearance, visible on the teapot's surface.

Photo: Chuang’s Tea, Yilan, Taiwan. Katrina Wild.

The clay undergoes a meticulous preparation process, involving extraction, crushing, cleaning, kneading, and sifting, followed by mixing. The final colour of the teapot depends on the clay's origin, depth of extraction, and the firing method used. A hallmark of a quality Yixing teapot is the clear, metallic sound it produces when tapped gently with its lid.

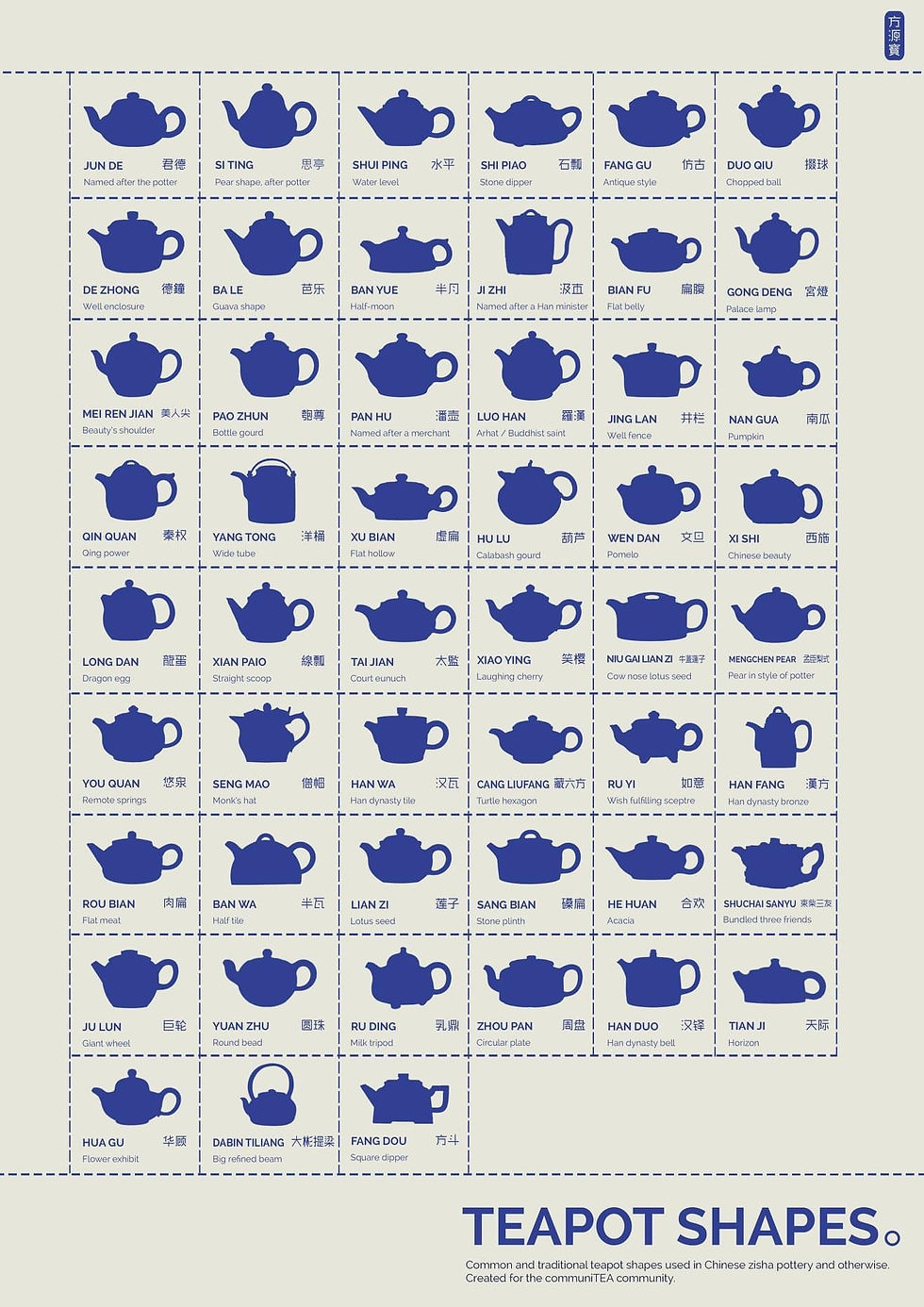

For a Yixing teapot used in gong fu cha ceremonies, the "three-level rule" is a sign of superior craftsmanship: the tip of the spout, the top of the handle, and the rim of the teapot should be level with each other. The lid should fit snugly to prevent movement, and the handle and spout should be perfectly aligned. Each teapot typically bears the potter's seal or signature, located on the bottom, under the lid, or sometimes beneath the handle, serving as a mark of authenticity and quality. There are many traditional shapes that the pottery apprentices have to master when practicing the craft of teapot making.

Pin Cha (品茶) and Gong Fu Cha (工夫茶)

Chinese tea brewing techniques are diverse, with each method highlighting different aspects of the tea's flavor and aroma. Pin cha (品茶), which translates to "tasting tea," is one of the most prevalent traditional techniques. Pin cha aims to reveal the pure taste of the tea without any ritualistic elements. The essential utensils for a Pin cha session include a chahe (茶荷, translates as «tea lotus») for measuring tea, a chaban (茶盘) or tea pool (cháchí, 茶池) for catching excess water, a gaiwan (盖碗) for brewing, a gong dao bei (公道杯) or fairness cup (also known as chahai (茶海, translates: «sea of tea») to ensure even tea distribution, and small teacups (茶杯). Tea towel (chájīn, 茶巾) or tea napkin (chábù, 茶布) — another optional but useful element of tea session. This method is simple and widely practiced in homes, tea shops, and tasting sessions, focusing solely on the tea's inherent flavours.

Photo: Bitter Leaf’s gaiwan, Latvia. Katrina Wild.

Gong Fu Cha (工夫茶), translating to "making tea with skill," is the traditional Chinese tea ceremony known for its meticulous and artful approach. This method involves using a small teapot (cháhū, 茶壶) or gaiwan and steeping whole leaf tea multiple times in short durations. Each infusion reveals new flavours and aromas, making Gong Fu Cha a gradual and immersive tea experience. This technique is particularly suited for high-quality ceremonial teas, and it offers a peaceful and contemplative way to enjoy tea, whether alone or with others.

Variations of Gong Fu Cha include the Taiwanese and Chaozhou styles, each with unique features. Taiwanese Gong Fu Cha often incorporates aroma cups (闻香杯, wénxiāng bēi) and tasting cups (品茗杯, pǐnmíng bēi) to fully appreciate the tea's fragrance and flavour. This style uses a set of two cups: the tall aroma cup captures the tea's scent, while the lower tasting cup is for drinking. Chaozhou Gong Fu Cha focuses on using Yixing clay teapots (宜兴壶) and often employs local techniques and preferences. Both variations maintain the essence of Gong Fu Cha, emphasizing skill and mindfulness in tea preparation.

Photo: China Tea Spirit.

Zhu Cha: Lu Yu's Boiling Method

Photo: Moychay.nl.

Boiling tea leaves is the oldest method of tea preparation, dating back to the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907 AD), where people would boil tea leaves for extended periods, often adding spices, herbs, roots, fruits, and even chili, salt, and scallions, and used as a healthy and tonic beverage. It was widespread in regions such as China, Mongolia, Tibet and in other parts of Asia. The tea boiling method was described by famous Chinese philosopher and tea master Lu Yu in his “Tea Canon”, the first tractate about tea traditions. The gradual extraction from the leaves during boiling allows for prolonged enjoyment. While puerh, hei cha, certain oolongs, and aged white teas benefit from boiling, green and black teas tend to become overly astringent, making this method less suitable for them.

Senchado and How to Brew Japanese Tea

Japanese Tea Ware

Japanese ceramics have a rich history dating back over 10,000 years to the Jomon period, where some of the oldest pottery in the world was created. This tradition evolved through the Yayoi and Kofun periods, with significant developments in kiln technology and artistic styles. By the Heian period, Japan had established distinct regional pottery styles, which further flourished during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods. This rich history culminated in the establishment of six ancient pottery kilns, each renowned for their unique techniques and contributions to Japanese ceramic art:

- Tokoname-yaki (常滑焼), Aichi Prefecture;

- Karatsu-yaki (唐津焼), Saga Prefecture;

- Bizen-yaki (備前焼), Okayama Prefecture;

- Shigaraki-yaki (信楽焼), Shiga Prefecture;

- Tamba-Tachikui-yaki (丹波立杭焼), Hyogo Prefecture;

- Echizen-yaki (越前焼), Fukui Prefecture.

Photo: From left Tokoname-yaki (mogake technique), Asahi-yaki, Shigaraki-yaki. Katrina Wild.

These kilns have been renowned for centuries for producing high-quality ceramics, including teaware, each with its own distinct styles and techniques. It's important to note, however, that many other regions in Japan also create exceptional pottery. For instance, Asahi-yaki (朝日焼) in Uji, Kyoto Prefecture, and Arita-yaki (有田焼) porcelain in Saga Prefecture are also highly celebrated for their craftsmanship and beauty.

— Kyusu (急須): A traditional Japanese teapot, typically made of ceramic or clay, used specifically for brewing green tea. Kyusu often have a side handle, which makes them unique and easy to use.

— Shiboridashi (絞り出し): A small, lidless teapot used for brewing high-quality green teas like Gyokuro and Sencha. It allows for precise control over the water temperature and infusion time.

— Hōhin (宝瓶): Similar to a kyusu but without a handle, this teapot is used for brewing delicate teas. Its design allows for slow, careful pouring to enhance the tea's flavour.

— Yuzamashi (湯冷まし): A water cooling pitcher used to lower the temperature of boiling water to the desired level for brewing green tea. This ensures that the tea is not scorched and maintains its delicate flavour.

— Yunomi (湯のみ): A traditional Japanese tea cup, typically taller and more cylindrical than other tea cups. Yunomi are used for everyday tea drinking, especially for green tea.

Photo: Japanese Tea Sommelier, Koto Tea, Pekoe and Imp, Tezumi.

What is Senchado (煎茶道)?

Photo: Ogasawara-ryu Senchado, Japan Tea Guide.

Photo: Bunjin-ryu Senchado, Nagasaki. Katrina Wild.

Tea ceremonies hold a special place in Japanese culture, offering a ritualistic experience where the host and guests come together in a tea room, celebrating the beauty of nature and seasonal changes. While many are familiar with sadō (茶道), the formal ceremony involving matcha, there is another tradition known as senchadō (煎茶道), which centers around loose leaf teas like high grade sencha, kabusecha, and gyokuro.

The origins of senchado trace back to a Chinese Buddhist monk Ingen (隠元隆琦) during the early Edo period (1603-1868), who brought Ming style tea culture to Japan in 1654 and built Manpukuji Temple in Uji, providing a more accessible tea drinking alternative to the formal chanoyu, which was reserved for the elite. Then, the spreading and popularising of sencha is attributed to the priest Gekkai Genshō, also known as Baisao (売茶翁), the "old tea seller."

This practice has traditionally been passed from teacher to student, with few written manuals available. The ceremony uses a teapot to infuse the tea leaves, and the utensils and manners vary by school and type of tea, adding to its rich diversity. One prominent instructor, Kaoru Nakai, teaches senchado at the Senryū-ji Buddhist temple in Kyoto. Her style is often performed for the imperial family during special occasions, such as the crowning of the prince or annual visits by the emperor.

Senchado features various styles and ceremonies, such as "kakubon no hiratemae" (standard ceremony with a square tray; 角盆の平点前), each with different trays and teaware. The main guest, seated to the host's left, receives tea first, followed by the other guests. A seasonal flower and a fan are placed between the host and guests as symbols of respect, and the ceremony begins with the lighting of incense. The host prepares and serves the first infusion of tea, followed by a sweet treat, typically higashi (a dry sweet made from sugar and rice flour; 干菓子). During the preparation of the second infusion, the host engages with the guests, answering questions and sharing insights. The second infusion marks the end of the ceremony, with the main guest usually declining additional tea as a polite gesture to signal the conclusion.

The host's movements in senchado are intricate, involving specific ways of holding utensils and pouring tea. The host carefully monitors the tea's strength, first pouring a bit into the last cup, known as the "host's cup," and tasting it to ensure quality before serving the guests.

I'm no Buddhist or Taoist, nor a Confucianist either, I'm a dark-faced white-haired hard-up old man. You think I just prowl the streets selling tea? I've got the whole universe in this tea caddy of mine.

— Baisao

Samovar: The Russian Tea Tradition

Photo: Samovar Museum in Varnja, Estonia. Visit Estonia.

The samovar, a traditional Russian tea urn, has a history dating back to the 18th century. It became a central feature of Russian social life, symbolising hospitality and comfort. To brew tea with a samovar, water is heated in the main chamber, while a small teapot with concentrated tea is placed on top. Hot water from the samovar is then mixed with the concentrated tea to achieve the desired strength. Outside of Russia, samovars are also widely used in countries like Iran, Kazakhstan, Baltic countries, and other East European and Central Asian regions, where they play an essential role in local tea culture. For instance, the Old Believers, Eastern Orthodox Christian communities, celebrate the enjoyment of tea in samovars, remaining a symbol of warmth and community, used during gatherings and daily tea rituals.

Turkish çaydanlık

Photo: GoTürkiye.

In Türkiye, drinking tea from traditional, tulip-shaped glasses has become a cherished way of life, enjoyed from morning until bedtime. In Turkish homes, a teapot is always ready to serve family and guests. Even during work, tea breaks in "çay ocağı" (tea houses) are common. To make Turkish tea, you'll need a special teapot called a çaydanlık, which consists of a large container for boiling water and a smaller one for brewing tea. You can prepare it by boiling water in the larger pot, then pouring it over tea leaves in the smaller pot, and letting it brew on low heat for 10-15 minutes. Alternatively, you can brew the tea and boil the water simultaneously by placing both pots on medium-high heat until the water simmers, then reducing the heat and letting it brew. This ritual not only provides a delightful beverage but also embodies the warmth of Turkish hospitality.

Occidental Methods: Western Tea Brewing

Photo: East Frisian Tea Ceremony. Lippe, Ostfriesisches Teemuseum Norden. German Commission for UNESCO.

Western-style brewing represents one of the simplest and most straightforward methods of tea preparation, typically involving a large teapot or infuser. This method is perfect for social gatherings, allowing tea leaves to steep and expand naturally, resulting in a highly aromatic and flavorful brew. Iconic examples include the British Afternoon Tea, where a large teapot is used to prepare black tea served with milk and sugar, and the East Frisian Tea Ceremony, known for its strong, sweet tea with cream. Unlike the multiple steepings in other tea cultures, Western-style brewing usually involves a single, longer steeping, after which the leaves are discarded. Additionally, the "grandpa method" offers a casual alternative, where tea leaves are directly placed in a large cup and repeatedly topped with hot water, providing a simple yet authentic tea-drinking experience without the need for strainers or teabags.

Chuyên Trà: Vietnamese Tea Ceremony

Photo: Kieu Thi.

Although not widely known, the Vietnamese tea ceremony, known as "Chuyên trà," deserves attention. This style of tea brewing emerged during the Later Lê Restoration period (1533 – 1789) and reached its pinnacle during the Nguyễn dynasty (1802 – 1945). Tea enthusiasts were meticulous in their selection of teapots, cups, kettles, and stoves, continuously striving to refine their understanding and brewing techniques. The practice was seen as a pursuit of virtuous individuals, providing a relaxing and spiritually nourishing experience known as “Thanh nhàn.” Tea is brewed by boiling water in a kettle, quickly infusing it in a small teapot, and serving it in thin teacups, resulting in a beverage with a rich, layered taste and a delightful aftertaste.

There are 16 utensils in Chuyên Trà, but let's focus on four of the most essential pieces of teaware:

- Ấm chuyên trà (Special Teapot): This thin-walled teapot, made from unglazed Yixing clay, has a fixed lid and a small capacity of 60ml to 160ml, perfect for brewing the delicate tea.

- Chén Tống and Chén quân (Cups): The Chén Tống, a large teacup, serves as a pitcher from which tea is poured into smaller cups called Chén quân. These small, eggshell-thin teacups, usually bright white, allow for the appreciation of the tea's color. Sets from southern Vietnam typically include three Chén quân, while northern sets have four.

- Siêu (Kettle): Made from terracotta or bronze, this kettle features a side handle and a thin, concave base for rapid boiling. It typically holds between 350ml and 550ml.

- Lò than (Brazier): This small, expertly crafted brazier fits into the terracotta or bronze kettle. Its deep fire chamber maintains burning charcoal embers, while airflow holes and a thick base prevent overheating.

Lễ Hội Trà Việt: the first Vietnam Tea Festival in Hoi An 2022. Kieu Thi. Katrina Wild.

For more detailed insights into Chuyên trà, visit the Kieu Thi website, where Huyen Dinh, Seth G, Dinh Ngoc Dung, and Tran The Mong Kieu are diligently preserving this vanishing art. Their research and passion promise to yield a comprehensive book on the subject sometime in the future. Keep an eye on this project!

Darye: Korean Tea Ceremony

Photo: Ven. Hyesung, chairwoman of the Korea Tea Board. Daewonsa Temple. Katrina Wild.

One of our previous blogs written by Lorela Lohan explored Korean tea, read HERE. In this article, you can learn about Korean tea ceremony darye, as well as the traditional ceramics such as Goryeo Celadon, Buncheong, and more.

Modern Innovations

Cold Brew and Icey Infusions

Photo: Nagasaki Ikedoki Tea's shiraore cold brew in Mt. Hoshisho, Oita Prefecture, Japan. Hario Mizudashi Bottle. Katrina Wild.

Drinking cold brews, iced teas, and ice infusions offers a delightful way to enjoy tea during warmer months. Cold brews, like those made with Hario cold brew bottles, involve steeping tea leaves in cold water in the fridge for several hours, resulting in a sweet, clean-tasting brew with less bitterness and retained antioxidants. Mizudashi (水出し) is a Japanese method similar to cold brewing, using only cold water and steeping tea leaves for 4-6 hours, ideal for making refreshing drinks overnight. Another technique is tea over ice cubes, where brewed tea is poured over ice to slowly meld flavours, nicely observed in unique vessels like Martini glasses, for instance. Lastly, the ice drip method, adapted from coffee brewing, involves ice-cold water dripping slowly through tea leaves, producing a distinct tea flavour in a lengthy but rewarding process.

Coffee Tools Turned Into Tea Utensils: Aeropress, Chemex, V60, and Syphon

Coffee tools like the AeroPress, Chemex, V60, and Syphon have found versatile applications beyond brewing coffee, proving their adaptability to tea preparation as well. The AeroPress, known for its quick and efficient brewing, can be used with tea by adjusting steeping times and water temperature. The Chemex, with its elegant design and use of paper filters, offers a clean and bright infusion for tea leaves, although adjustments may be needed due to differences in particle size compared to coffee grounds. The V60, similar to Chemex in pour-over method, allows for precise control over brewing parameters. Meanwhile, the syphon, originally designed for coffee, making it ideal for robust teas like black, puerh, white tea, some oolongs, or herbal varieties and funky blends.

Photo: Shu puerh with dried orange in a syphon at a wedding, Latvia, Katrina Wild. Liene Pētersone.

Comments